How to Choose a Project

This text is an adaption from many sources, including Brett Mensh, of Optimize Science, Gay Hendrik’s The Big Leap, and content from 80,000 hours.

In many areas of life we often have to choose a “project”. This comes up in academia all the time in grant writing. A natural question therefore is how choose, that is, by what metric shall one choose a project. Here, I argue that the only three dimensions worth considering are: feasibility, significance, and passion.

Feasibility: Feasibility characterizes the probability that you can complete the project given your current resources and/or constraints. Your resources includes your background knowledge, the wealth of all previous knowledge that you have access to, resources that other individuals, collaborators, etc. are willing to invest on your behalf, and possibly facilities (such as computing facilities for our work). Constraints include your time, and the energy you are willing to invest in the project, given other life interests.

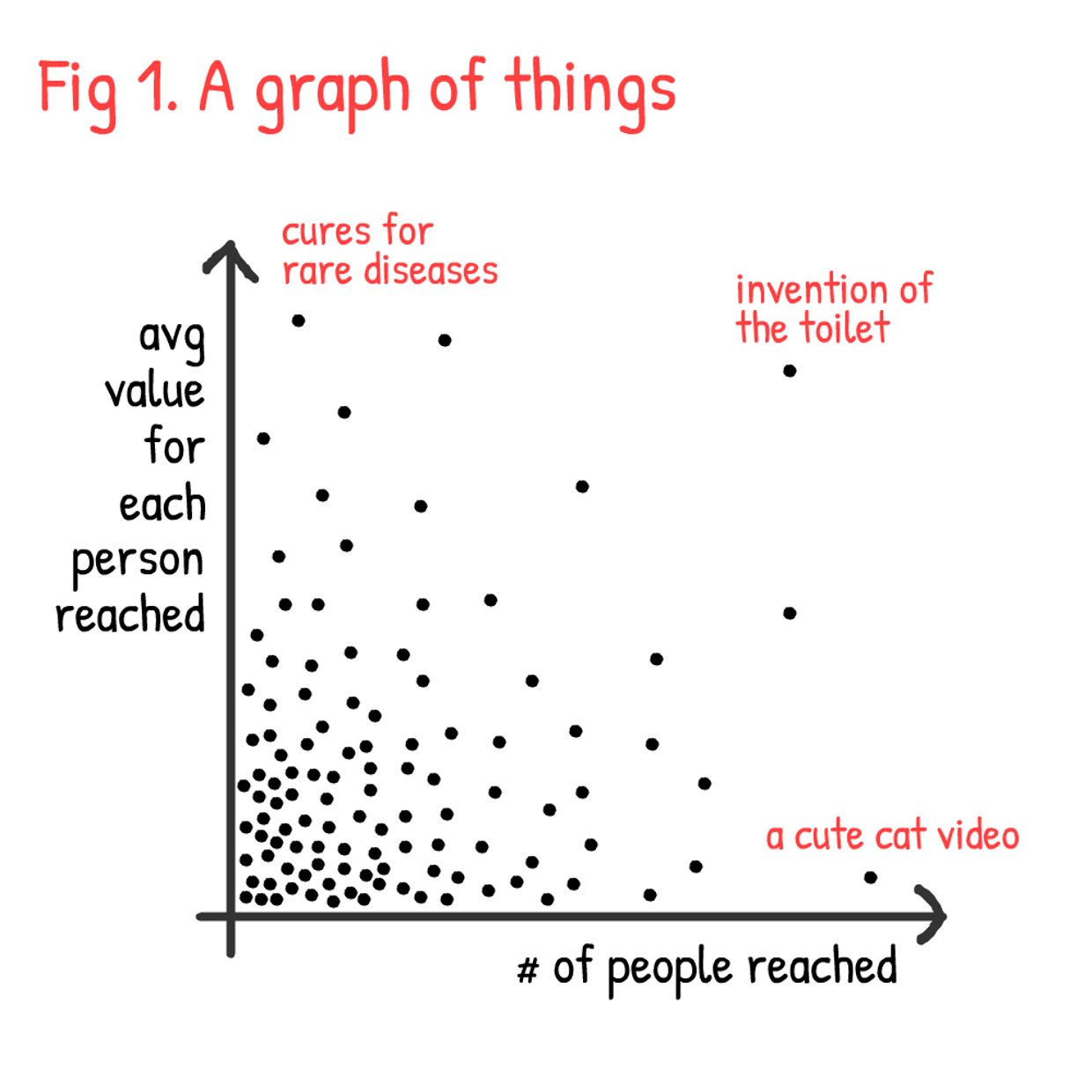

Significance: Significance characterizes how important, for the world, successful completion of the project will be. The equation for this is “# of people impacted x impact per person”. There is a wonderful little summary of this concept available here, which includes the following graphic:

. There is no optimal balance between these two factors. For example, consider a surgeon. She has huge impact on all the lives she saves, but the impact on the other 7 billion or so people is relatively small. On the other hand, consider somebody who makes a new popular game or music video. This can directly impact a billion people, to make them each a little happier. Under reasonable assumptions about the value of a single human life versus a few minutes of watching a video, neither is inherently more significant than the other. We each get to choose the relative balance of # of people vs impact on each person.

. There is no optimal balance between these two factors. For example, consider a surgeon. She has huge impact on all the lives she saves, but the impact on the other 7 billion or so people is relatively small. On the other hand, consider somebody who makes a new popular game or music video. This can directly impact a billion people, to make them each a little happier. Under reasonable assumptions about the value of a single human life versus a few minutes of watching a video, neither is inherently more significant than the other. We each get to choose the relative balance of # of people vs impact on each person.

Intrinsic Motivation: This dimension, how intrinsically motivated you are about the project, is less explicitly requested, but at least as important in determining your success. A bunch of research indicates that the more intrinsically motivated somebody is about a project, the more likely she is to complete it excellently. We can try to justify these internal feelings, and reason about them, but we need not. The goal here is to really “know thyself”, to estimate which kinds of activities are most motivating. A reasonable heuristic to use here to ascertain how you spend your “free time”. In other words, which global problems do you read about, protest about, get engaged about, or otherwise find interesting. And what kinds of activities to you actually enjoy: teaching, coding, writing, problem solving? This dimension is arguably the most difficult and most worthwhile to understand.